Blog posts

CAREPATH: Converting Polypharmacy Guidelines into Computer Interpretable Rules

Published on 28 December 2022Aging population have got greater attention by a multitude of organizations, notably in the World Health Organization (WHO) report” Global Health and Aging” in 2011 [1]. The number of people aged 65 or older is projected to reach 1.5 billion in 2050, from 524 million reported in 2010. Chronic noncommunicable diseases are one of the biggest burdens on health and on the health care systems. Older patients tend to suffer from so called multi-morbidity illnesses, i.e., the presence of many diseases or disorders that exist concurrently with a primary disease. This is challenging in multiple aspects for health care professionals and leads to increased usage of health care resources [2][3]. This leads to more complicated and/or multiple concurrent treatments, which usually lead to long-term use of multiple drugs in combination [4][5], called polypharmacy. Furthermore, the vast majority of older people including those with cognitive diseases are living at home and are cared for by informal caregivers also for long term. In Germany these are 80% [14], in other European countries the situation is similar [15], so informal care is to be seen as playing a pivotal role in the long-term care for older people. This high percentage fulfils the wish of many older people to remain living at home as long as possible. Countermeasures to issues arising from polypharmacy are urgently required, as polypharmacy is common in elderly patients [6] and care at home requires systems to monitor possible complications to ensure patient safety and provide a better medication prescription. Therefore, in CAREPATH, we focus on potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIPs), and translated a rule-based system into machine-readable form to automatically detect possible adverse events. Polypharmacy is defined as the concurrent use of multiple (usually more than four) medications or, sometimes, as the unnecessary use of multiple and/or redundant medications [7]. As mentioned before, this is common in adults older than 65 years, which shows that generally more than half of all patients older than 65 years take more than 5 prescription drugs [6]. The situation is complicated further by over-the counter medications. Studies regarding such medications show that, especially in certain communities, 90% of the patients take more than 1 and almost 50% take 2 to 4 of these over-the-counter medications [6][8]. Multiple clinical guidelines and screening tools have been developed to check for PIPs.

Which Polypharmacy Guidelines are useful?

Mark Beers et al. created a list of medications that can be considered inappropriate for older patients in long-term care in 1991 [09]. Beers’ criteria were updated regularly and are the basis for other criteria sets, most notably” Screening Tool of Older Persons potentially inappropriate Prescriptions” (STOPP) and” Screening Tool to Alert doctors to the Right Treatment” (START). Both are evidence-based lists of criteria, first published in 2008 and developed in Ireland by a round of experts using the Delphi consensus method [10][11]. Version 2 of these criteria was published in 2014 [12]. STOPP/START resulted in much research interest, many countries and institutions support the tools and consider them appropriate for evaluating prescriptions [13]. Here is an example of the STOPP criteria: The following prescriptions are potentially inappropriate to use in patients aged 65 years and older for cardiovascular system:

Risks and Threats

The AI-enabled healthcare space deals with a huge amount of medical data which is considered as treasure trove by hackers and is frequently under cyberattacks. Since individuals from different departments might require access to electronic health records, they are mostly web-based making them vulnerable to these attacks. Additionally, the use of legacy software and outdated IT security policies can leave systems vulnerable to external attackers. External threats are not the only concern, sometimes negligent or untrained staff can cause a data breach unknowingly.

- Digoxin for heart failure with normal systolic ventricular function (no clear evidence of benefit).

- Verapamil or diltiazem with NYHA Class III or IV heart failure (may worsen heart failure).

- Beta-blocker in combination with verapamil or diltiazem (risk of heart block).

- And here is an example of the START criteria for the respiratory system

- Regular inhaled agonist or antimuscarinic bronchodilator (e.g. ipratropium, tiotropium) for mild to moderate asthma or COPD.

- Regular inhaled corticosteroid for moderate-severe asthma or COPD, where FEV1 <50

- Home continuous oxygen with documented chronic hypoxaemia (i.e. pO2 <8.0 kPa or 60 mmHg or SaO2 < 89

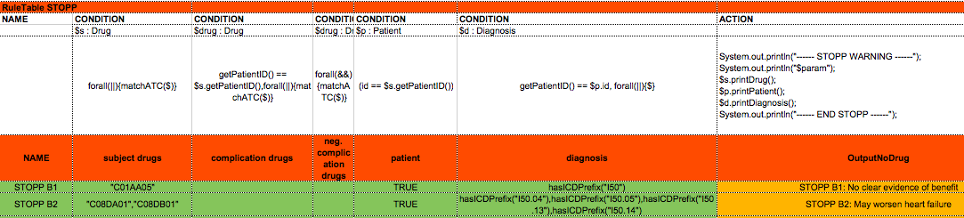

The guidelines were translated into computer interpretable rules as shown in the example in Figure 1

Figure 1: The template code of the STOPP decision table

How to Design a computerized Polypharmacy Service?

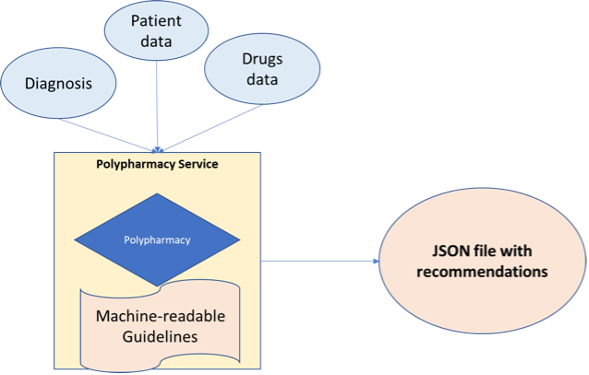

The Polypharmacy service prototype was designed with usability of the clinical guidelines for clinical professional’s focus, to have a structured and easily manageable representation of the machine-readable rules, without losing too much precision in detecting rule violations or losing too much flexibility in the addition of rule conditions and the manipulation of rules.

As shown in Figure 2, the system was designed as a self-contained service, with various possibilities for interoperability with the rest of the CAREPATH system in mind e.g. direct calls or REST API.

It is important to note that CAREPATH engine is used in a stateless fashion. Stateless sessions can be called like a function, a batch of data is passed to the session and the results of the rule executions are sent back. The production rule system does not keep track of (generated) knowledge and the result of one rule execution will never trigger or influence the execution of other rules.

Figure 2: Overview of CAREPATH’s polypharmacy service

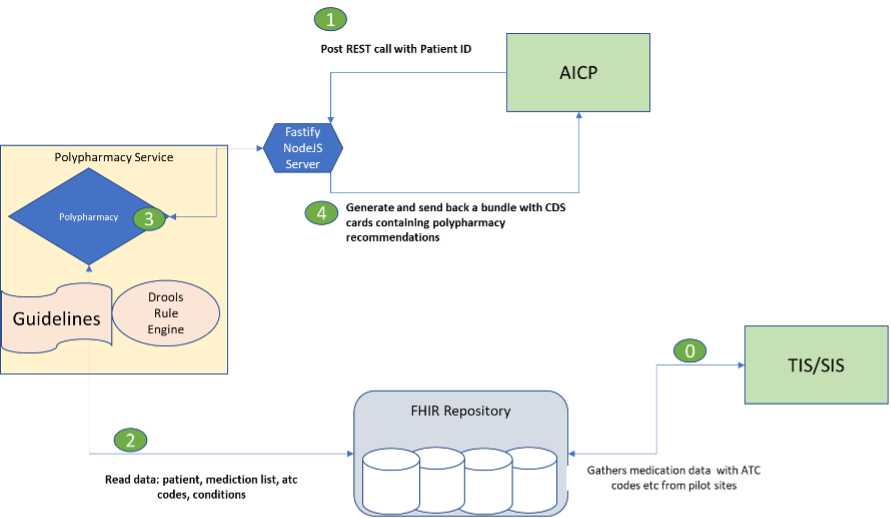

Integration of Polypharmacy into CAREPATH’s system’s workflow

The overall service is described in Figure 3, (0) starts with CAREPATH’s interoperability service (Technical Interoperability and Semantic Interoperability Suites, namely TIS and SIS), that gathers medication data of the participating patients in the clinical study. The CAREPATH polypharmacy (1) receives a REST API POST call with the patient id, the polypharmacy service (2) reads all relevant information about a patient and provides feedback about drug interactions, and interference while under certain therapies or suffering from certain diseases, as defined in the CAREPATH extended STOPP/START criteria. Depending on whether a START or STOPP condition is detected, an alert is given or a recommendation for therapy will be generated (4). The information is sent back to the AICP (Advanced Integrated Care Plan) to be used for care plan management, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Workflow of the CAREPATH polypharmacy service

Not shown in the workflow diagram is the process of looking up medications’ ids, from the electronic health record of a patient is used to get detailed information about a drug (more specifically about the active substance) and its classification in other coding systems such as ATC, which is currently used in the system so far. Finally, information about the medication of the patient and her diagnosis is used. If available, more precise information such as dosage of specific drugs, duration of the treatment and lab values can be used to give better feedback.

Reference:

- World Health Organization, “Global health and aging,” Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011.

- B. Starfield, K. W. Lemke, R. Herbert, W. D. Pavlovich, and G. Anderson, “Comorbidity and the use of primary care and specialist care in the elderly,” The Annals of Family Medicine, vol. 3, no. 3, 2005, pp. 215–222.

- T. Lehnert et al., “Health care utilization and costs of elderly persons with multiple chronic conditions,” Medical Care Research and Review, vol. 68, no. 4, 2011, pp. 387–420.

- K. Moore, W. Boscardin, M. Steinman, and J. B. Schwartz, “Patterns of chronic co-morbid medical conditions in older residents of us nursing homes: differences between the sexes and across the agespan,” The journal of nutrition, health & aging, vol. 18, no. 4, 2014, pp. 429–436.

- G. Kojima, “Prevalence of frailty in nursing homes: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, vol. 16, no. 11, 2015, pp. 940–945.

- E. R. Hajjar, A. C. Cafiero, and J. T. Hanlon, “Polypharmacy in elderly patients,” The American journal of geriatric pharmacotherapy, vol. 5, no. 4, 2007, pp. 345–351.

- S. P. Stawicki and A. Gerlach, “Polypharmacy and medication errors: Stop, listen, look, and analyze,” Opus, vol. 12, 2009, pp. 6–10. Copyright (c) IARIA, 2018. ISBN: 978-1-61208-608-8 21 FUTURE COMPUTING 2018 : The Tenth International Conference on Future Computational Technologies and Applications

- S. I. Haider, K. Johnell, G. R. Weitoft, M. Thorslund, and J. Fastbom, “The influence of educational level on polypharmacy and inappropriate drug use: A register-based study of more than 600,000 older people,”Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 57, no. 1, 2009, pp. 62–69.

- M. H. Beers et al., “Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents,” Archives of internal medicine, vol. 151, no. 9, 1991, pp. 1825–1832.

- P. Barry, P. Gallagher, C. Ryan, and D. O’Mahony, “START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment)—an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients,” Age and ageing, vol. 36, no. 6, 2007, pp. 632–638.

- P. . Gallagher, C. Ryan, S. Byrne, J. Kennedy, and D. O’Mahony, “STOPP (screening tool of older person’s prescriptions) and START (screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment). consensus validation.” Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther, vol. 46, no. 2, Feb 2008, pp. 72–83.

- D. O’Mahony et al., “STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2,” Age and Ageing, vol. 44, no. 2, 2015, p. 213. [Online]. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu145

- B. Hill-Taylor et al., “Application of the stopp/start criteria: a systematic review of the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults, and evidence of clinical, humanistic and economic impact,” Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, vol. 38, no. 5, 2013, pp. 360–372. [Online]. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12059

- Nienke Lindt, Jantien van Berkel and Bon C. Mulder. 2020. Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: a systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 20,304. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01708-3

- Evi Willemse, Sybyl Anthierens, Maria I. Farfan-Portet, Oliver Schmitz, Jean Macq, Hilde Bastiaens, Tinne Dilles and Roy Remmen. 2016. Do informal caregivers for elderly in the community use support measures? A qualitative study in five European countries. BMC Health Serv Res, 16, 270. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1487-2

This project has received funding from the European Union’s

Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant

agreement No 945169

This project has received funding from the European Union’s

Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant

agreement No 945169